Countless meetings and workshops to review each team’s processes and requirements. Navigating politics, personalities and egos to land on a plan that earns the buy-in of the combined team. A holistic view of upstream and downstream processes to identify and mitigate change impacts. These are all important contributions to a successful M&A integration strategy.

But there’s one factor that doesn’t get enough airtime in merger integration: finding assumptions. Not challenging assumptions – literally finding where they exist before they derail a smooth integration.

Hidden assumptions can take many forms, but they’re usually the most innocent oversights in integration planning that can have outsized effects. These are the practices, usually informal, that are baked into the processes of the business through the cumulative experience of the team. The things that have always been done one way, and there usually isn’t even an inkling that there is another way. With both teams unaware, it doesn’t come up in workshops or in process documentation.

The Equivalent System Assumption

Take this simple example in a recent acquisition, where the acquiring team was focused on completing a migration across a pretty typical systems landscape. Plans were completed and work was well underway to migrate the target’s CRM to the acquirer’s CRM and retire the target’s system.

“You guys got the contracts too, right?” asked a member of the target team.

The Legal team wasn’t involved in the CRM migration. Besides, it was assumed that the target’s contracts would just be stored and managed with the acquirer’s contracts.

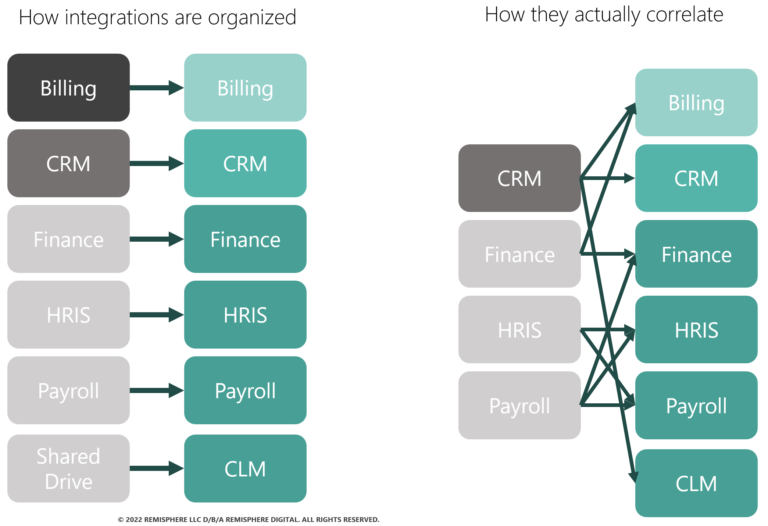

It turned out that the target’s operations team, however, was accustomed to storing all of a customer’s contracts as attachments in their CRM system. Both sides simply assumed their way was standard, and nobody had thought to ask if there might be a different practice. This is probably the most common hidden assumption: that both companies use equivalent systems for equivalent business processes. It’s rarely a one-for-one correspondence, as illustrated below:

Hidden assumptions can be in any business process, but here are three other areas where the hidden assumption can sneak up on your merger planning:

Period close processes – The month-end and quarter-end close is a dark art. Revenue recognition, reconciliation and journal posting: everybody’s following GAAP or IFRS principles, right? Buried in a consistent outcome are the judgment calls, automations and rules of thumb that might not have the same level of rigor or interpretation in both organizations.

Compensation and payroll practices – You’ve both got hourly and salaried employees. Apples to apples and oranges to oranges, right? Harmonize compensation, line up the payroll dates and you’re done. But wait, are the hourly folks paid in arrears or based on estimated hours? When can hourly rates change and for what work? Are timesheets rounded to the nearest hour? What about exempt status, is that consistent?

Quote to cash – How is pricing calculated and approved today, and can you replicate that method in the new system? Is the number that the salesperson is paid on going to be there too? If you keep some aspects separated, what happens when you want to cross-sell? Which legal entities are involved in a cross-border sale?

So how do you identify these hidden assumptions? By their nature, they’re hard to find. Here are a few ideas:

Ask open-ended questions, then listen.

Often, we will use workshops to ask targeted questions that help us drill into what we need to know about a process. This discovery process is important and it takes a skilled facilitator to get the important details captured. But too often we ask questions that give us exactly the answers we’re looking for, but don’t leave the room for open-ended conversation and exploration that might flag something we didn’t think to ask about.

- “What are some of the other things you do in the system we haven’t talked about yet?”

- “Are there any exceptions or workarounds you know about?”

- “How often would this information change? Who would decide/approve and when?”

- “Are there any processes that go on hold when someone is on vacation?”

Build both technical and functional process flows.

Build two versions of business process flow charts – one team and process focused, and another that is systems-focused:

- The first functional flow has swimlanes for each team (or sometimes person) and each item corresponds to a business task, e.g., “Generate quote” or “Approve pricing”

- The second, technical flow should have swimlanes for systems, and each item corresponds to an action or data flow in the system, e.g., “Upload pricing template” or “Download usage report”. This works best when you ask the process owner to demonstrate their process steps in a recorded session.

Line up these process flows and reconcile them to make sure there’s nothing missing or misaligned. If they line up perfectly, you’re good. If not, you’ve probably found a hidden assumption.

Because it’s likely at least some of your processes will be changing as a result of the integration, creating these for both as-is and to-be states is important. In the event the post-merger process will look different than either company’s prior process, you’ll need three sets. It’s time-consuming, but there is no better way to bring together process-oriented, data-oriented, visually-oriented, and task-oriented personalities to a single conversation.

Run a quick pilot, and do it early

It may not always be practical, but sometimes the best way to develop a design is to perform some very basic configuration and ask the current process owner to execute their process in a “dev” or “QA” instance of the to-be system. This level of rigor isn’t always a part of merger integration scenarios, but even the process of generating one quote, one bill, or posting one journal entry during the design and planning phase will smoke out gaps that may need to be addressed.

There’s no way to completely avoid surprises – there are simply too many moving pieces and personalities to capture every last nuance, but taking proactive steps to find the “practices” in the “processes” will go a long way in identifying what’s below the surface.

Do you have any techniques you’ve used? What do you think? Join the conversation on LinkedIn.

Copyright © 2022 Remisphere LLC. All rights reserved. Unauthorized duplication or usage without permission strictly prohibited.